Before the Heart Attack: What Actually Shows Up First

Two patients. Same week. Two very different rooms. Both diagnoses felt sudden. Neither one was. One patient sat across from me in clinic. The other came to me through a phone call from the North Slope.

Both stories started years earlier than the moment I met them.

Kyle is 47. Two years older than me.

A friend. A patient. Someone I’ve known long enough that when he sat down and said, “Jake, I need to tell you something,” I could hear the concern before the words landed.

For three or four months, he’d been getting short of breath. Just slightly. Only sometimes. No associated chest pressure. He especially noticed breathlessness going up stairs.

One flight was harder than it used to be. Two flights sometimes meant stopping.

His resting heart rate, once in the 70s, now lived in the 90s and he would notice his heart rate jumping into the 120s with minimal effort.

Kyle then told me he felt embarrassed. He thought he was just out of shape and that he had almost talked himself out of coming in.

Then he said a statement that sank in deep:

“I’m worried I might have one of your conditions.”

Next, before we talked about tests, we talked about his history.

Kyle’s history looked “pretty normal” by traditional standards. His blood pressure was usually running in the high 130s over 80s.

His cholesterol had been slowly creeping up: total cholesterol in the 220s, LDL in the 130s, rising about 5-10 points every year since he began following his labs. Triglycerides in the 110–120 range. HDL in the low 40s.

Kyle’s family history wasn’t catastrophic but it wasn’t benign:

A grandfather with a heart attack in his 40s

Diabetes in multiple family members

An aunt with a stroke

He’d been seeing his primary care clinician most years. The message and instructions had been consistent:

Lose five or ten pounds. Eat a little healthier. Walk more.

“You’re probably okay.”

When we ran his numbers through standard our risk calculators including PREVENT he landed just below the threshold where guidelines tell us to act.

On paper, he was borderline. In real life, he was symptomatic.

So we stopped looking at calculators and started listening to his body.

Two days later, I was on call. The call came from the North Slope. A 49-year-old mechanic, Justin. Two weeks on, two weeks off. Sometimes more. A family of four. Kids in middle school. wife holding everything together while he was gone.

Justin never had chest pain before.

That day, working indoors not outside in the Alaska cold performing heavy labor, he felt pressure in the center of his chest. It radiated to his jaw. His left arm felt numb, then painful.

He tried to convince himself it was a sore muscle from his bench-press workout a week earlier.

But it kept coming back.

Hours later, the PA in the small clinic did an EKG.

ST elevations on the ECG in the anterior leads.

A large myocardial infarction.

Emergency protocols moved fast: thrombolytics (clot buster), antiplatelets, anticoagulation (blood thinners) & emergency transfer to Anchorage.

When I met Justin, he was pain-free, but not out of danger.

In the cath lab, the picture was clear:

99% proximal LAD lesion

Successfully stented

Mild anterior wall hypokinesis

Ejection fraction 45–50%

Justin was lucky.

Looking backward through his history, the gaps were obvious. He didn’t see a doctor regularly. His blood pressures, when checked, were usually in the 140s over 80s.

He didn’t know his cholesterol numbers.

His father had a heart attack in his 50s.

His mother had a stroke later in life.

No one had ever told him he was high risk.

Both of my patients asked me, “Am I too young to have heart failure… or a heart attack?”

Neither of these stories started with heart failure. Or a heart attack.

They started with signals.

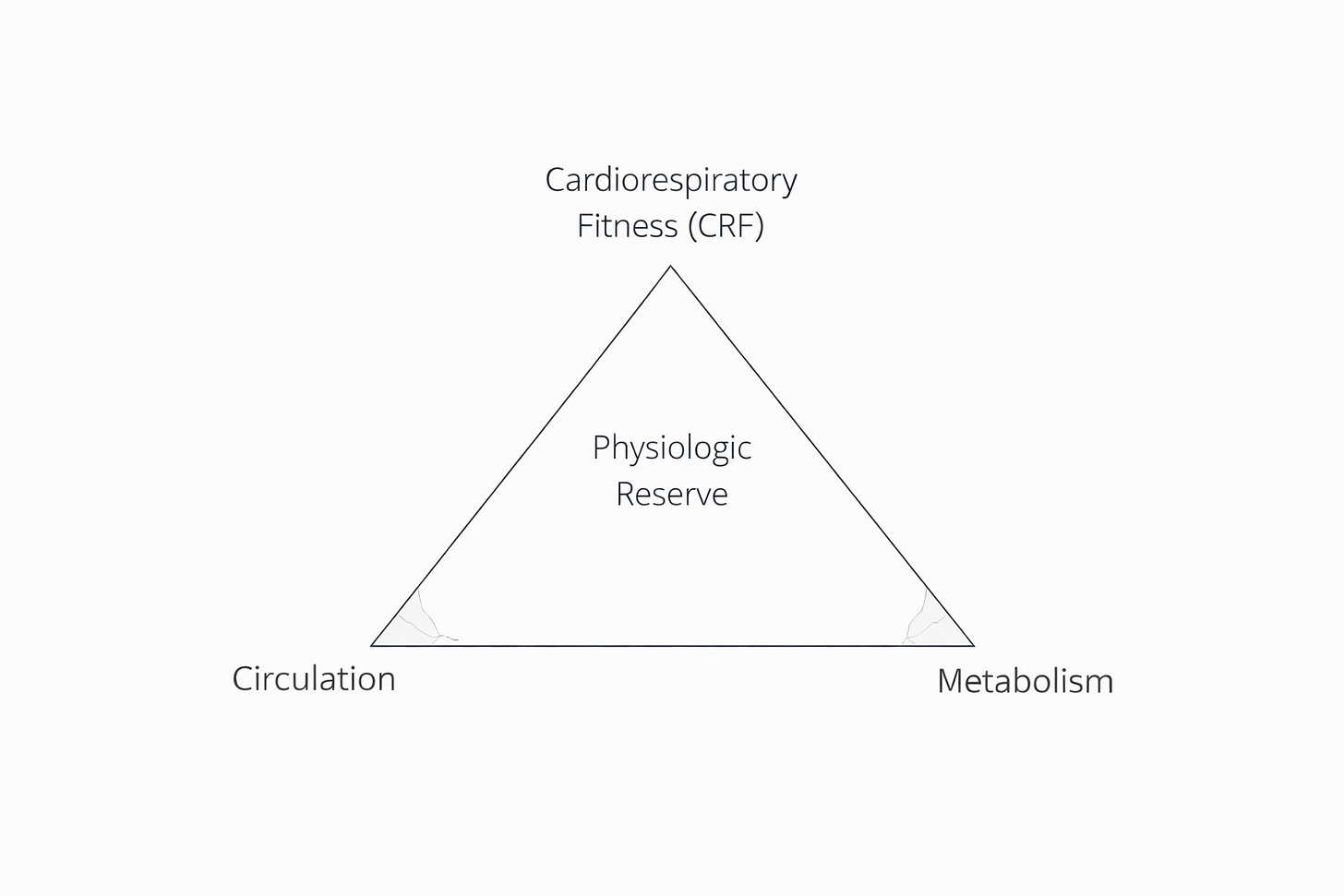

As I look backward now, I see both patients through a simple framework I use every day: a triangle:

Circulation (atherogenic burden)

Metabolism (insulin resistance, visceral fat)

Cardiorespiratory fitness (physiologic reserve)

Most of us focus on the top of the triangle only after the bottom two sides have already cracked.

The first patient, Kyle, almost certainly had years of quietly rising atherogenic particle burden that could have been noticed if we looked deeper into his circulation and the bloodstream’s underlying particles.

LDL cholesterol alone often misses this. ApoB tells us how many particles are actually circulating and interacting with the arterial wall, long before symptoms appear. This has been shown repeatedly across genetic, epidemiologic and outcomes data.

Lp(a), had we measured it, may have revealed inherited acceleration through cardiovascular risk that no amount of “trying harder” could offset.

The second patient, Justin the mechanic, likely had years of cumulative exposure as well. Elevated blood pressure. Family history. Dyslipidemia (abnormal cholesterol) that was never measured seriously enough to matter.

Different paths. Same underlying biology.

Neither of my patients had diabetes. But both showed signs of abnormal metabolism or metabolic stress long before any diagnosis.

Triglycerides drifting up.

HDL drifting down.

Weight redistributing centrally.

Insulin resistance precedes diabetes by years: often decades. By the time glucose rises, the damage is already underway. And no one had ever measured waist circumference, which is a crude but powerful marker of visceral adiposity that often outperforms BMI for cardiometabolic risk.

These are not exotic insights.

They’re early signals.

Neither man lacked motivation or ignored his health.

They were failed by when we chose to act.

That distinction has changed how I practice.

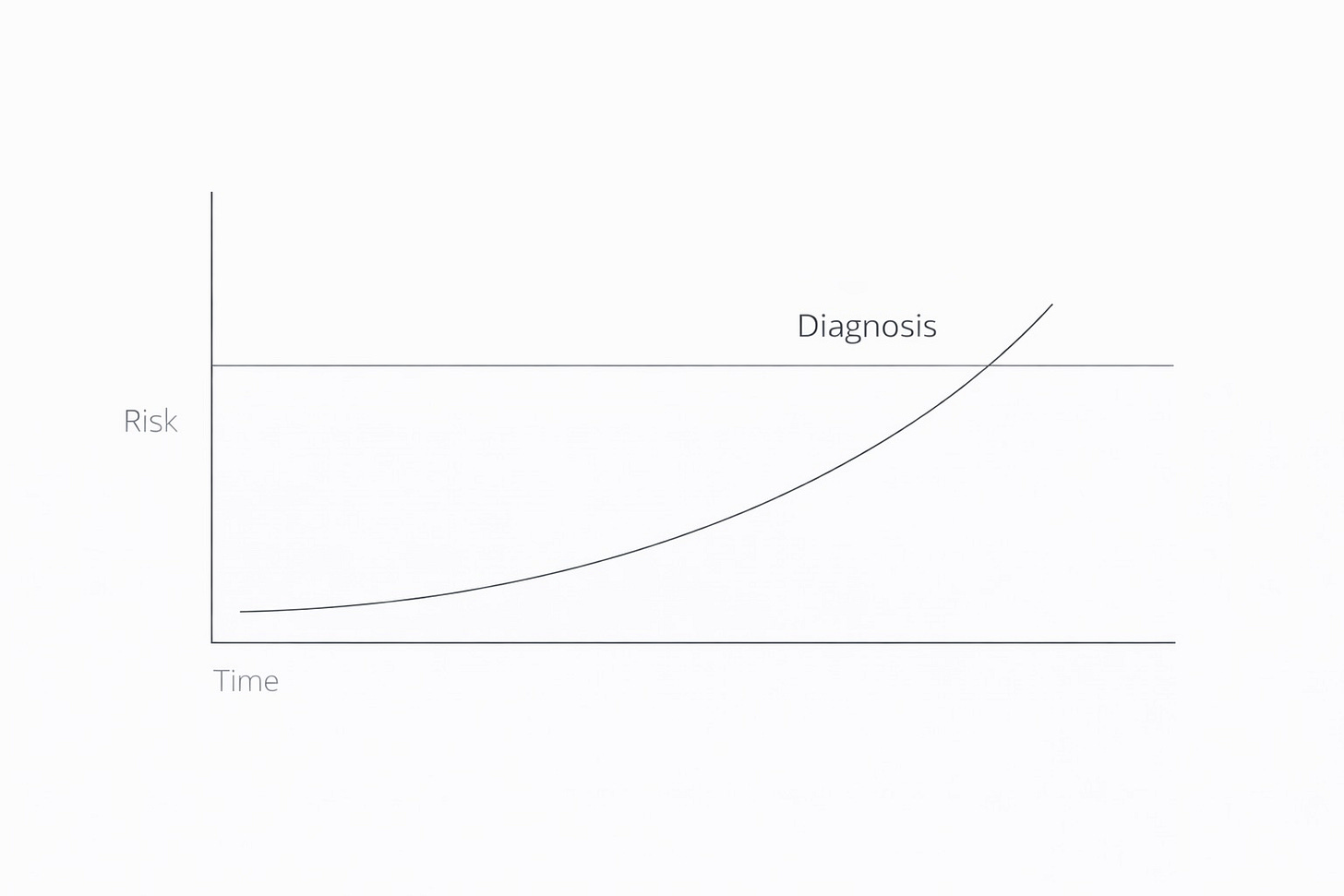

Late diagnoses tell us disease is present.

Early signals tell us disease is forming.

ApoB isn’t an “advanced lab.”

Lp(a) isn’t exotic.

TG:HDL isn’t perfect… but it’s early.

Waist circumference isn’t elegant; it’s honest.

These are early warning lights, not boutique tests.

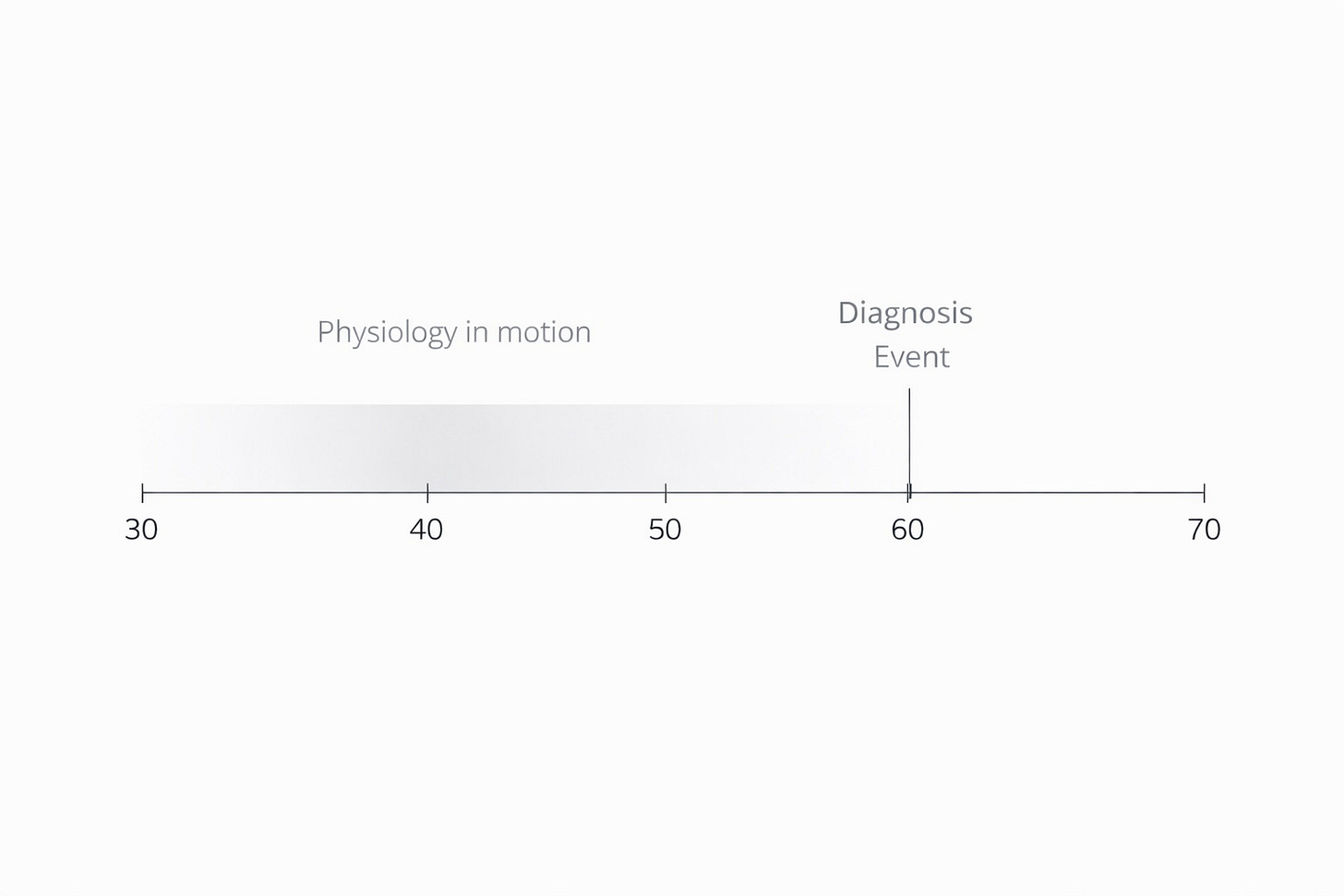

Guidelines are built around thresholds.

Physiology moves along trajectories.

By the time we cross a threshold, the curve is already steep.

Could we have prevented this?

That’s the question I keep coming back to.

Could we have changed the trajectory for my friend in clinic before his left ventricle dilated to 6.2 cm and his ejection fraction fell to 25–30%?

Could we have changed the slope for the mechanic before his LAD closed down?

I believe the answer, at least some and maybe most of the time, is yes.

But only if we’re willing to look earlier.

Waiting for events isn’t conservative medicine.

It’s a failure of imagination.

If we intervene earlier, targeting circulation and metabolism first, we often improve the third corner of the triangle automatically.

Physical activity (at least 150 minutes per week).

Sleep (a real goal of 7–8 hours per night).

Stress (reducing chronic load, not eliminating life).

Nutrition (real food, adequate protein, vegetables, fruit and metabolic consistency).

Layered thoughtfully and supported by medication when needed, these interventions don’t just lower risk factors.

They raise capacity.

In my next article, I’ll re-introduce the single number that consistently outperforms all of these markers when it comes to predicting longevity and why improving circulation and metabolism almost always pushes that number in the right direction.

For now, this is the takeaway I want to leave you with:

Heart attacks and heart failure don’t come out of nowhere.

They come from signals we chose not to measure or monitor.

Find your baseline.

Move the needle.

Track it.

Change the trajectory.

That’s real medicine.

That’s Medicine 3.0.

—Jake

References

Ference BA, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(32):2459-2472.

Sniderman AD, Thanassoulis G, Glavinovic T, et al. Apolipoprotein B Particles and Cardiovascular Disease: A Narrative Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(12):1287-1295.

Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925-3946.

Ross R, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2020;16(3):177-189.

Lopez-Jaramillo P, Gomez-Arbelaez D, Martinez-Bello D, et al. Association of the triglyceride glucose index as a measure of insulin resistance with mortality and cardiovascular disease in populations from five continents (PURE study): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4(1):e23-e33.

Chen Y, Chang Z, Liu Y, et al. Triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and cardiovascular events in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;32(2):318-329.

Spot on my man. I see the same trends in the PT clinic regarding both orthopedic and general deconditioning scenarios. The Ernest Hemingway quote comes to mind when he asked how he went bankrupt- “Gradually, then all of the sudden.”

The signs are there for your health, but you have to 1. Know what to look for 2. Actually look 3. Act accordingly.

Thank you for elevating the conversation to treatment prior to crisis!

Would love your thoughts about women and heart disease and how to prevent the dismissive treatment that so often greets women presenting with the same symptoms.